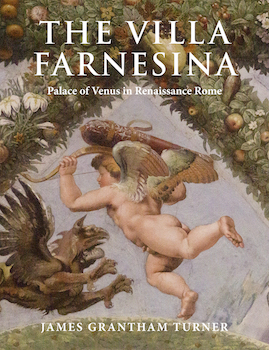

Professor James Grantham Turner’s The Villa Farnesina: Palace of Venus in Renaissance Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2022) studies in depth, for the first time in English, a building that has enraptured admirers from Rubens and Fragonard to Goethe and Edith Wharton — a villa that Turner compellingly evokes as the most beautiful dwelling of the Renaissance. Drawing on a treasure trove of evidence, much of it neglected or unknown, from documents, drawings, archaeological traces, and parallels in other projects connected with the commissioner Agostino Chigi and his precocious painter-architect Peruzzi, the book brings to life the achievement of the building and its famous frescoes. It studies the Villa Farnesina literally from the ground up and from its earliest origins, while also establishing the cultural forces that converged there: the creative interaction of architecture, poetry, painting and landscape, Chigi’s patronage and love of antiquities, his literary influences, and the perceptions and meanings generated by his interpretive community.

Turner suggests that, while Agostino’s villa-palazzo might display his personal horoscope – the aspect most studied by Aby Warburg and others – it also expresses his self-made interests and pleasures. Astrology is less important as a unifying theme than the power of Love, the evocation of Eros and Venus – the goddess of aesthetics as well as erotic pleasure, as Chigi’s poets well understood.

In this post Turner shows how the Villa has dazzled its many visitors (from 1512 to the present) and tells us about the “detective work” he did to restore its original meaning and splendor.

The author ‘standing’ in his digital reconstruction of the original Villa Farnesina garden and east façade

When is a Villa like a Hawk? The Renaissance theorist and architect Leon Battista Alberti imagined houses as living beings: when they are happy they welcome you to their “bosom,” the central hall; when they are badly sited they feel humiliated, “enjoying no dignity” and “taking no pleasure.” Gendered as feminine, the building loves to “gaze out” at her surrounding landscape: spectabitur, spectabit, she is “both a spectacle and a spectator.” Other thinkers wrote that “all buildings want to be luminous” – as if they actively desire the light – and that they “surge” upward. Giorgio Vasari, a founding figure in art history, said of the Villa Farnesina that “it seems to be not built, but truly born.” Translators of Alberti’s Latin expanded this idea of living, gazing architecture even further: the house yearns to take in the landscape “as if it were a Hawk to look clear round about, and constantly refreshed on every Side with delightful Breezes.”

Vasari’s raptures about this villa, on the bank of the Tiber in Rome, were not the first: one French diplomat acclaimed it “the most beautiful and rich thing I have ever seen” as early as 1512. (“Bank” is a kind of pun, as it was commissioned in 1506 by the world’s wealthiest banker, Agostino Chigi, who was also a gifted connoisseur with an unerring eye for the talent of artists and writers.) This much-visited jewel of the Renaissance has been written up many times, but I am the first to reconstruct the whole estate as conceived and created in 1506-1520, identifying everything it has lost and reinterpreting its best-known masterpieces by Raphael, Sodoma, Sebastiano del Piombo and Baldassare Peruzzi (the astonishingly young architect who “gave birth” to the whole villa and also painted many of its frescoes). I show how Peruzzi gave Chigi’s low-lying villa that hawk-like uplift and command of the view, emphasizing the open rooftop belvedere (now half-demolished, walled in and closed to the public) that once yielded glorious views of the river and the seven hills of Rome. And I restore those “delightful Breezes” – with the help of the poets who described the vital interaction of the green, scented gardens and the airy loggias, before they too were shut in. Ever since I was a student I’ve been fascinated by how art, literature and landscape architecture interact: I found in the Farnesina a perfect example of a “green world” where all the arts flourished together – though now it’s reduced to a shell preserving only its famous frescoes, sitting in a modern garden much smaller than the original. A 19th-century embankment sheared off most of the grounds.

Palace of Venus in Renaissance Rome … that’s the subtitle of my book and one of its central themes. For many years I’ve worked on the history of sexuality and how Antiquity and ancient mythology were rediscovered – allowing some to imagine a secular life of refined hedonism: Chigi’s artists embodied this vision. In my 2017 book Eros Visible I called the Farnesina “the seedbed of an erotic revolution.” The goddess Venus appears in almost every room, and was once prominently displayed on the outside, nude and locked in a passionate embrace with Mars. Venus brings together aesthetic and erotic pleasure, the “hawklike” delight in the environment and the sensuous pleasure of love: the poets imagine her moving in, appreciating the ornament, rushing excitedly upstairs to the roof to enjoy the view, bathing with other gods in the pool, and wishing she had been born there. Agostino lived openly with his mistress Francesca, who bore him three children before they finally married. For their wedding he commissioned three new frescoed rooms swarming with lovers from myth and history, Cupid’s spouse Psyche and Alexander the Great’s bride Roxana. In the nuptial bedroom Sodoma’s Roxana expresses “transcendent voluptuousness” (as a later visitor put it), “throbbing with powerful life and seeming to effuse a most delicate perfume.”

Visitors enjoying Sodoma’s bedroom fresco … with closeups

Tributes to the Farnesina’s “harmony and pure beauty,” its “airy loggias” and “miraculous” painted rooms, echo down the centuries: “painting and poetry truly most beautiful … full of visual wonder and delight. … Agostino gathered there everything beautiful and precious that Nature could give, everything artistic that the mind could invent.” Goethe, Zola and Edith Wharton idealized the place; Rubens, Fragonard and Turner went there to sketch. Voluptuous nudes, flying gods and cupids, lifelike vegetation and illusionistic “prospects” increase the sense of floating away into an enchanted world. One of the pleasures of a stay in Rome was walking down from the American Academy with our poet-laureate colleague Robert Hass, who is also a keen naturalist. As he entered the villa for the first time his wondering gaze shot upwards to the vault of the Psyche Loggia, through the amazing fictive pergola of fruit and foliage to the blue sky populated with closely-observed birds and mythological creatures that look just as realistic.

Visitors awed by the Psyche Loggia … and details from the ceiling

What survives is only a fraction of this most creative house, however. Visitors (and some scholars) seem unaware of what has been lost. The exterior paintings have vanished, the gardens have been washed away and built over, open loggias have been sealed so they can no longer breathe. Large areas of the extant building also remain underinterpreted, preventing our understanding of the whole, the total work of art “gathered” by Chigi and his team of artists, poets and intellectuals. This book is therefore a ghost story and a detective story.

I first visited the Farnesina when it housed the national collection of prints and drawings, and got to know the brilliant head of restoration Rosalia Varoli. Back then it looked on the outside like your typical Italian villa, painted orange-ochre with patches of picturesque decay, and after years of cleaning it’s now smooth and whitewashed. But when Vasari and the Chigi Pope Alexander VII saw it the whole exterior was animated, painted with mythological creatures looking out into the glorious landscape and erotic scenes that resembled sculptures with a warm light playing across them – “very beautiful” and “noble,” matching the dazzling interior. I started to connect the fragments, filling in the hints and findings of earlier scholars, to visualize what this decorated exterior looked like.

Detective work became part of the adventure. Though I write for the general reader as well as the specialist, my endnotes are packed with thorough scholarship, examining every document and published source in ten languages. The visual documentation draws upon some ninety-five sites, museums, libraries and private art collections. But I also probed the villa itself and what is left of the grounds. For example, only a stump remains of Raphael’s first venture into architecture, but I show that it was a grand hotel for visitors, upstaging the villa itself – not just the “stable” as it’s often called. I spent many summers scampering up and down dusty bricked-up staircases to discover the original circulation-patterns and connections between rooms, poking my camera boom through a tiny aperture in a store-room to find the remnants of a frescoed ceiling, plumbing the depths (literally, with a line and sinker), snooping around the back garden to find a magnificent carriage gate, tapping on walls to find the hollow spots where a cheerful fireplace must once have been – the focus of every room, as Alberti cleverly put it. I undid later remodelling and placed walls and ceilings in their original positions, to recreate convivial rooms, well-proportioned, well-lit and welcoming in all seasons. All my discoveries show how Peruzzi achieved effects of grace and organic unity by close attention to foundations, basements, servants’ quarters, fireplaces and chimneys, communicating doors, attics and the vertical circulation of staircases. This hands-on research confirms that the Farnesina was a true dwelling, properly heated, ventilated and secured, rather than a mere “summer retreat” for occasional visits, as many have thought.

We know that Agostino “loved all virtuosi” and invested in all the arts, including music: I reconstruct the actual recital room and the instruments played there, adorned by Peruzzi with dancing Muses and the gods of Music. We know that Agostino sponsored the first Greek printing press in Rome: I show which room it was housed in. We know that Agostino’s poets celebrated the “shining” and impressively vaulted lower ground floor, especially its luxurious marble-clad steam baths: I crawled into basement recesses to find the furnace that supplied hot water, and I reconstruct exactly where this private bathing-suite was situated. We know that Agostino staged boating parties and fabulous banquets on the edge of the river: I reconstruct the form of his colonnaded dining pavilion and the grotto and bathing pool beneath it. The most beautiful villa of ancient Rome lay buried under Chigi’s grounds, but it was officially only discovered in 1879 by a team excavating the foundations of the new Tiber embankment that destroyed most of the gardens; I find direct echoes of those ancient paintings in the Farnesina itself, showing that Chigi and his artistic team had discovered them underground.

Details from Peruzzi’s bedroom ceiling and from the ancient Roman villa found underneath the Farnesina

So my book lets the visitor and the reader imagine the brilliant milieu that “gave birth to” the Farnesina, the literature that celebrated it, the artistic rivalries that stimulated fresh invention, the graceful proportions of the original architecture, and the great gardens that once made this villa the most famous beauty spot in Rome. Hundreds of my own photographs and digital reconstructions, as well as images never published before and close-ups of details freshly brought to light – all these provide a personal guided tour, with virtual glimpses of the vanished façade-paintings, orange groves, fountains, grotto, pool and banqueting-pavilion. No wonder Venus wanted to make this place her own.

How the Villa Farnesina looks now

How it might have looked at first